We've come a long way you and I.

On this day two years ago I was nervously hammering out the

final details of the episode on the Franco-Prussian War that would make up my

very first official episode. I had just got my guest episode published on the History

of England Podcast that covered the Battle of Bannockburn, which technically

meant that the podcast was ready to go, considering that the exposure gained

from HOE would hopefully pull in new viewers and raise awareness. All that was

needed was for me to release new episodes on my own bat. It was a shaky start.

Initially my podcasting skills were as bad as my graphic design skills, thankfully my podcast skills have improved, though I can't say the same for my graphic design skills.

I had very little real idea what I was doing and pretty much

just copied everyone else who I admired and who I had spent so much time

listening to during my periods of travel or exercise or anything else that I

could use as an excuse to have to put those earbuds in yet again and devour my

favourite show. In the years before I had come to love podcasts, and I would

tell anyone who'd listen how great, approachable and effective they were as a

means of learning. It didn't matter if I wasn't taking a test on the subject

matter or if I was or wasn't studying the historical era in question in

college; what mattered was that somewhere across the world, an individual was

taking time out of his life to actually tell me something I didn't know, to

teach me something new. What was more, they (most of the time obviously)

enjoyed it.

Despite the clear amount of work they required, and the

other life they definitely had, podcasters were happy to tell me about the ins

and outs of Trajan or the food people in Medieval England liked to eat while

also doing important life stuff. Not only that, but these podcasters weren't

historical rockstars, they were average joes who had the drive and skills

necessary to keep up a show and keep up their life at the same time. They would

then be subjected to love that they would share on their shows. I would hear

their experiences, and more and more the idea began to creep in that I could

try my hand at it too.

I don't remember the exact date. But I knew what I wanted to

do. I knew for a fact that most history podcasts that focused on wars usually

bored me. They didn't focus enough on why wars happened, mostly they seemed

content to tell us why unit A killed unit B and how they did it. For some

people, this was the best thing ever, but for me I wanted to know why; why was

unit A so determined to kill unit B in the first place, and furthermore, what

did unit C think of all this? It drove to me examine what I really looked for

in history, what I really enjoyed more than anything else. I knew I liked

looking at the background of wars, and I always relished the chance to read

about those really important ones that most people didn't really know about. When

reading about wars I would always skim past the military stuff and look more

carefully at the buildup to the war in question; I loved examining the

relationship between states and how it came to deteriorate over time, or how

certain statesmen drove certain policies that tied a state to a certain course

of action. I realised, a little bit to my surprise, that I really enjoyed

learning. What better way to learn, I mused, than to put what I discover into a

form everyone else can get enjoyment from? A Podcast.

I'm still your average photogenic guy who loves Lord of the Rings marathons through the night just as much as podcasting and historical pursuits.

But could I really do it? I had no idea how the sound made

by those I listened to even reached me. I didn't know enough about hosting or

recording or anything. Literally all I knew was that I liked certain things

about history and that finding them out and sharing them with others gave me

that intense warm fuzzy feeling you get when you open a door for a pregnant

lady. I had so much to learn, so I hit up Google and I started to panic. 'THIS

is why loads of podcasts on the topic I want to do doesn't exist', I lamented.

'Just look at the amount of jargon I have to learn!' I filled pages of refill

pad paper as I sought to teach myself what everything meant, and how I could go

about making one myself. I set out a list of what I would need and how much

it'd cost, then I worked a way out where how much I would have to pay someone

to do all the boring and technical stuff for me. At this stage, 'boring and

technical stuff” still included typing out the script and editing the sound file

after recording it. I was clueless.

Yet I persevered, mainly because I sought additional help

from an experienced podder. From the moment I heard his ad for a guest podcast

I felt inspired. I milked the whole 'gimme just a little bit of help from one

podcaster to another' thing for so long it wasn't funny. I managed to persuade

him to listen to my draft recording of the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn as a

guest episode for him, and he was on board. I'm not exaggerating when I tell

you that I listened to David Crowther say my name on his podcast over ten times.

This was David Crowther; the man who had led me personally through English

history for the past year; and now he was announcing that I was due to guest

appear on his show. I'm sure he thought I was a fantastically clueless and

eccentric history nerd, but that didn't stop him from taking a well-deserved

rest that week and letting my guest show be put on instead. Eventual my robotic

episode on Bannockburn went up on the History of England feed. By that time I

had the concept: wars throughout history, but from a diplomatic perspective. I

had the plan: prepare a few episodes in advance, then release them and test the

waters. I also had a name: When Diplomacy Fails.

With the feedback and experience from Bannockburn and the

goodwill of the internet I penned Bismarck's best adventure and then sought to

supplement it with something different. I was aware of TALK format episodes; it

was in fact the Napoleonic Podcast by J David Markem and Cameron Riley that

gave me the idea (to essentially plagiarise them), but I wanted them to really

support my individual efforts, in case people were actually bored with me but

still liked the subject. It worked surprisingly well as a concept. The choice

of Sean was natural since he was my besty (and though I forced him to endure

repeated rapid historical learning against his will he still is), but we had to

make sure we gelled. I didn't want it to be this awkward giggle fest where only

we really understood what was going on (though I understand some people do

simply see the episodes as that) because I wanted them to still possess the

ability to inform someone of the historical topic. I wanted at the same time to

show that I was a normal person just as comfortable in front of a mic in a

closed room as I was with my best friend after having eaten too much food.

People appeared to have taken to it. I can't say how much people genuinely

listen, but to this day TALK episodes (as they came to be known) usually

receive 3/4 of the downloads that the regular episodes get. I rarely receive criticism

for them (perhaps people just aren't willing to be mean?) and have been told

that our banter is a welcome break from the style of the solo episodes.

Benjamin Ashwell in particular was kind enough to point to our TALK episodes as

one of the motivators for him selecting a similar format for his now very

popular podcast on the Italian Unification.

Sean and I will always find an excuse to goof around when we're aren't doing some serious TALK episodes. Credit to him, he never complains!

The summer of 2012 saw me really grow as a podcaster, even

though personally it was a very difficult time for me. Right around the time of

WDF 4: The Spanish American War, my Dad collapsed from an aortic aneurysm while

on holiday with family in Spain. The details were sketchy at first, but since

it was my duty originally to mind the house over that ten day holiday, I was

home alone, and I remember receiving that phone call while in church, a week

after they had left. 'Dad has collapsed' was all Mom was able to say. I still

remember that Sunday night, when details were sketchy and I was trying to

distract myself while in denial of the whole thing. I was trying to record the

Spanish-American War episode when the doorbell rang. From where I was sitting I

could see who was at the door waiting for it to be opened: numerous friends of

the family. I could also see the stern looks on their faces. I'll never forget

that feeling. Panic doesn't even describe it. It was like the world was

swallowing me, and I wanted to go away to somewhere where none of this was real

anymore.

I opened the door. I fully expected them to say that Dad had

died. Those were the words I expected to hear as they led me back into the

sitting room, made me sit down and breathed in deeply. But those words didn't

come. Instead I was told that he'd be having open heart surgery, that this

meant they wouldn't be coming home as normal but that everyone would make sure

I was going to be ok. It's funny now when I think of it, but because I expected

the news to be so much worse I was overjoyed at the news that my Dad was having

massive surgery in a foreign country I was far happier than they expected, to

the point where I think somebody thought I had simply pretended not to hear or

didn’t really understand the news. I thanked them for their time and led them

to the door. I started recording again and the tears began to flow mid-record.

I stopped recording and I just cried and cried. I got a drink of water and I

cried some more. So many feelings poured out at once. I was so relieved,

because I just knew he'd be ok, but I was also so scared and alone. I prayed

like I'd never prayed before, and I went to sleep in that room on that couch

clutching my dog tightly and thanking God for my family. I finished that

episode a little later than deadline, which I think I allude to but I don't

explain why. This, in case you were wondering, was why. I still have yet to

listen to that episode. Sometimes even seeing that episode in the podcast listing

makes my eyes well up again.

As a listener you may not want to know the above, but what

happened to my family in the early days of my podcast really formed part of

this podcast's identity. Dad came back from Spain virtually in pieces, with a

beard for the first time (that I had seen at least) and having dropped serious

poundage. Opening the door to his shell was something I'll never forget either.

But I made sure not to let the events of that summer deter me. My podcast was

so often my escape from these feelings, and when I didn't feel like I could go

on without my family I would read more into wars I'd like to cover in the

future. Gently, slowly, I would keep myself going until everyone finally came

home safe and sound. For some reason I remember that on the day they came home

I had just passed 13,000 downloads, but I'm pretty sure I didn't mention it

till much later.

Myself and Dad a few months later. Still my hero.

When I started 2nd year in college it became obvious that

college was, realistically, going to get in the way of When Diplomacy Fails. So

I sought to ignore college for as long as I could. I succeeded, and actually

churned out a good few episodes that autumn, but soon exams beckoned and not

for the first time I had to put WDF on hold. I knew I was crazy when on

Christmas Eve I was applying the finishing touches to the episode on the First

Italo-Ethiopian War, but I loved every moment of it. The year 2013 was due to

be special for me, because I had a plan, to finally cover the first world war

in the detail I felt it never got, from the ground up. My 10 part special on

WW1 took me about 6 months to complete, including initial prep and college

interference, but it was so totally worth it. All it really did was whet my

appetite for the era in general, but it also provided me with a really good

example of how the podcast can further my knowledge. I was so delighted; as my

downloads grew and my traffic increased, that so many people loved what I was

doing. At this stage I finally felt I had found my niche. This was professed by

a local Wicklow listener Sheamus Parle, who sought me out to speak at the

Wicklow Rotary Club on podcasting and what I am and why on earth I do this, in

January 2013. It was a great, triumphant experience for a Zack who had never

tried proper public speaking before, and throughout it everything that could

have gone wrong didn't, which made me think that maybe, teaching wouldn't be

such a bad gig for me after all. Such were the areas future job ambitions grow

from.

So 2nd year in UCD finished without much incident. But soon

I realised that the 2nd podcast summer I had predicted would not materialise.

Though I had the topics planned and I was gearing to go, I had finally got

myself a part time job in my local Costa Coffee, and it soon became clear that

it would take all of my time. Though I would be paid, I would find juggling

podcast and job very difficult and very frustrating to adapt to. That summer I

released far less than I wanted, but I learned a valuable lesson. Well a few

actually. You can't always podcast when you want; sometimes you have to put the

tedious stuff first; preparation is key; sometimes I can be unnecessarily lazy

and sometimes podcasting was my favourite thing in the world to do.

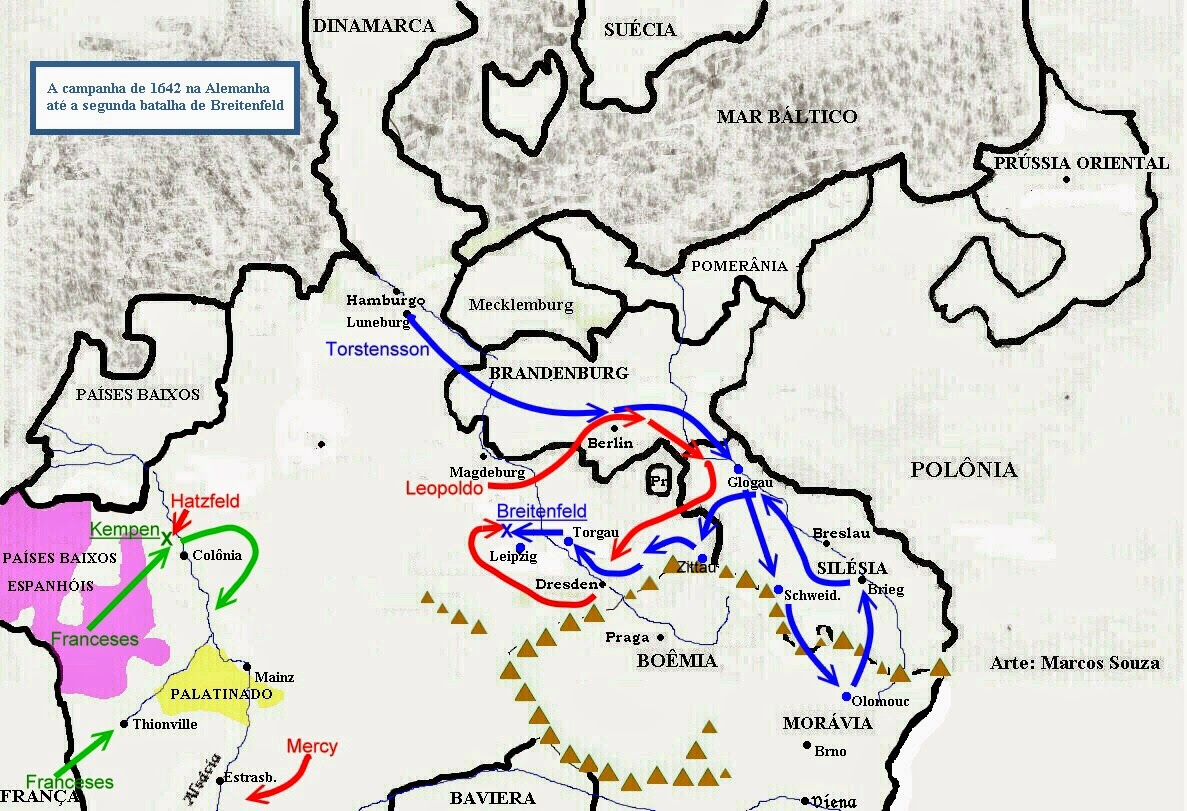

But the podcast stayed alive, and I remained determined to

keep up at least an acceptable level of podding while I viewed the final year

of my Bachelor of Arts coming into focus. I had begun the process of examining

the 30 Years War, and I knew that if it was going to work I had to manage a

system where college and podcast could coexist. To an extent I did, but it was

certainly helped by the fact that I finally found a history subject I really

enjoyed. 3rd year was the year in my history studies when it felt

like I wasn’t just struggling against the subjects in history I was forced to

do. My history module ‘Politics, Culture and Diplomacy in Post-Westphalian

Germany’ was so up my street I was practically living in it. The descriptor of

the module made it sound like it began in 1648, at the end of the 30 Years War

that I happened to be covering at the time. In actual fact though, it began

earlier, as far back as the beginning of the 1500’s, and pretty much covered

everything I loved about history in its duration until it sadly ended 12 weeks

later with Napoleon. It was this course that reinvigorated my interest in

history and made me determined to pursue it both academically and via podcast. The

previous two years of mediocre subject matter and tired historical teaching had

been made up for in this short term of learning.

Finally announcing that I had a part time paying job was a proud moment for me, but the war between job and podcast was unfortunately about to begin

Though the work was hard, we of course managed to have some fun time, below is my main man Stephen and Michaela, along with me of course

I managed to acquire an A grade in my Germany module;

confirming at least in some way that it was the right direction for me. I quite

simply loved what I was doing. It was a great feeling, even if I couldn’t

release as many episodes as a wanted. That Christmas time in between my exams I

was contacted by another listener to speak, this time to a legit college

audience about the background to the European Union. It was quite the task, and

I definitely spent more time preparing my guest lecture for John Hogan’s

politics class than I did studying for my semester one exams. But I’d like to

think it was worth it. The lecture went amazingly well, and I had that kind of

euphoria afterwards that one only gets when they do something they love and

they do it well. It helped of course that I had been seriously nervous about it

for weeks beforehand. It also helped that I got to do some serious Christmas

shopping afterwards. It also helped that I got paid for my troubles. Thanks

again Dr Hogan, not only did you bring me out of my academic shell but you gave

me the confidence to realise that, not only could I possibly teach in the future,

but I am also justified in doing this podcast since I actually am qualified to

bring people on this journey of learning.

Giving a guest lecture to these poor souls was a seriously proud moment for me, and the support I achieved from Dr John Hogan and the staff at the Dublin Institute of Technology spurred me onwards to pursue my interests further.

Also in that semester I was made aware that one of my old

school friends had been asked while doing science grinds if he knew anyone who

could do history grinds for Junior Cert level (about 15-16 year olds). This old

friend of mine had seen and heard noise about my history podcast, and had heard

along the grapevine that I was something of a history enthusiast. He

recommended me to teach this poor girl history grinds. I now teach history

grinds and get paid to do it. This is my first teaching job and I seriously

enjoy it. Sometimes I think I scare the poor girl with my enthusiasm for things

that happened 100 years ago. Like the podcast though I always try to keep it

fun. At least I don’t tell her to BEFIT. Yet.

The New Year saw me struggle with work, college and

podcasting, with the latter unfortunately coming dead last when it came to time

allocated to it. I sought to release episodes in pairs so the story would

hopefully flow a little better, and I think it worked even if it meant the

process took longer. I always made sure I was satisfied with the product before

I released it. Facing into my finals was tough, but all I could think about was

far I’d come, how far the podcast had come; how far we’d all come. I plan on

doing my Masters in International History in September, mostly so those who ask

“who the hell are you anyways to talk to me about this topic” can please be

quiet, but also because I wanted to further my learning. My podcast had taught

me that the subjects I enjoyed were worth pursuing, since other people liked to

hear me talk to them about what I’d learned, and the cycle would never end. I

felt like I owed it to myself not to doubt what I was capable of, but to look

at the idea of a masters with the same attitude as I had the podcast; a

challenge that I could tackle, and that I was determined to overcome.

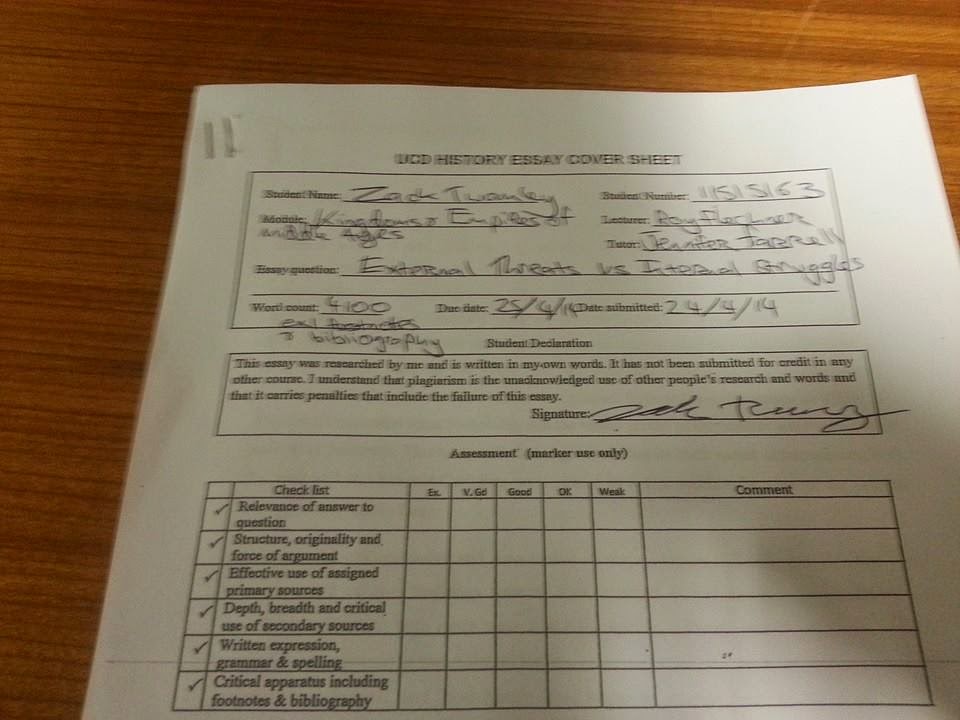

The photo of my final UCD college essay as an undergraduate, recorded for posterity.

Trying to put my finger on exactly what I had learned in my

two years of podcasting is difficult. But I know that I have seriously

benefited from it. I remember listening to a wrestling podcast, the Art of

Wrestling by Colt Cabana, and on it he said that the best thing you can do as a

creative person is have something you can point to as all your own, as your

baby and your own creation; something that nobody else can take away from you

and something that will always stand as a credit to you. I really feel that.

Through the toughest times, even when I was snowed under with work, stresses or

family troubles the podcast was always the thing I could hold up in my mind as

something I could be proud of, something that, no matter how low my

self-confidence went, would be there representing my efforts and mine alone.

When Diplomacy Fails has made me over 1,000 euro in

donations. It has given me the opportunity to give a guest presentation and a guest

lecture in a college. It has enabled me to practice my teaching methods with

history grinds. But these are just the practical things. It has networked me

with some incredible people, connected me with some seriously grateful and kind

listeners; where I had the opportunity to advise them on setting up their own

podcasts themselves. It was instrumental in helping me to further my learning

and deepen my understanding of what I really enjoyed in history. I have been

listened to in countries across the world, by people who don’t even have

English as their first language! It is my proudest achievement and my favourite

thing to do. It has taken over 60 hours of content, over 100,000 words and over

half a million downloads to do it, but When Diplomacy Fails and the people who

love it are a big part of the reason I am who am I today. In the space of two

years, you and I have been through a lot. We’ve seen a lot of wars together; we’ve

seen stupid mistakes, hilarious blunders, interesting side-notes, dastardly

villains and terrible jokes. At the end of these two years though, I’d like to

think that as the podcast has improved, so have I; not only as a podcaster or

even amateur historian, but also as a man, as a son, and as a friend.

Not bad for a nervous 20 year old kid who had no idea what

he was doing.

So, here’s to two years more, and more and more and more!

Zack Twamley, BA. (I had to get that in there).

Nothing is more important to me than family. (from left to right: Joanna, Sarah, me, Mom, Dad)

.jpg)